State of the PI

This week I presented my annual “State of the Lab” talk to my research group 1. This is generally an opportunity for me to show the lab how I see the role of each member, various projects fitting together, our financial situation, and my plans for the coming year. It’s also a bit harrowing because I always fear that I’ll leave someone out. This time around, I started by reporting that I feel better than I have in months.

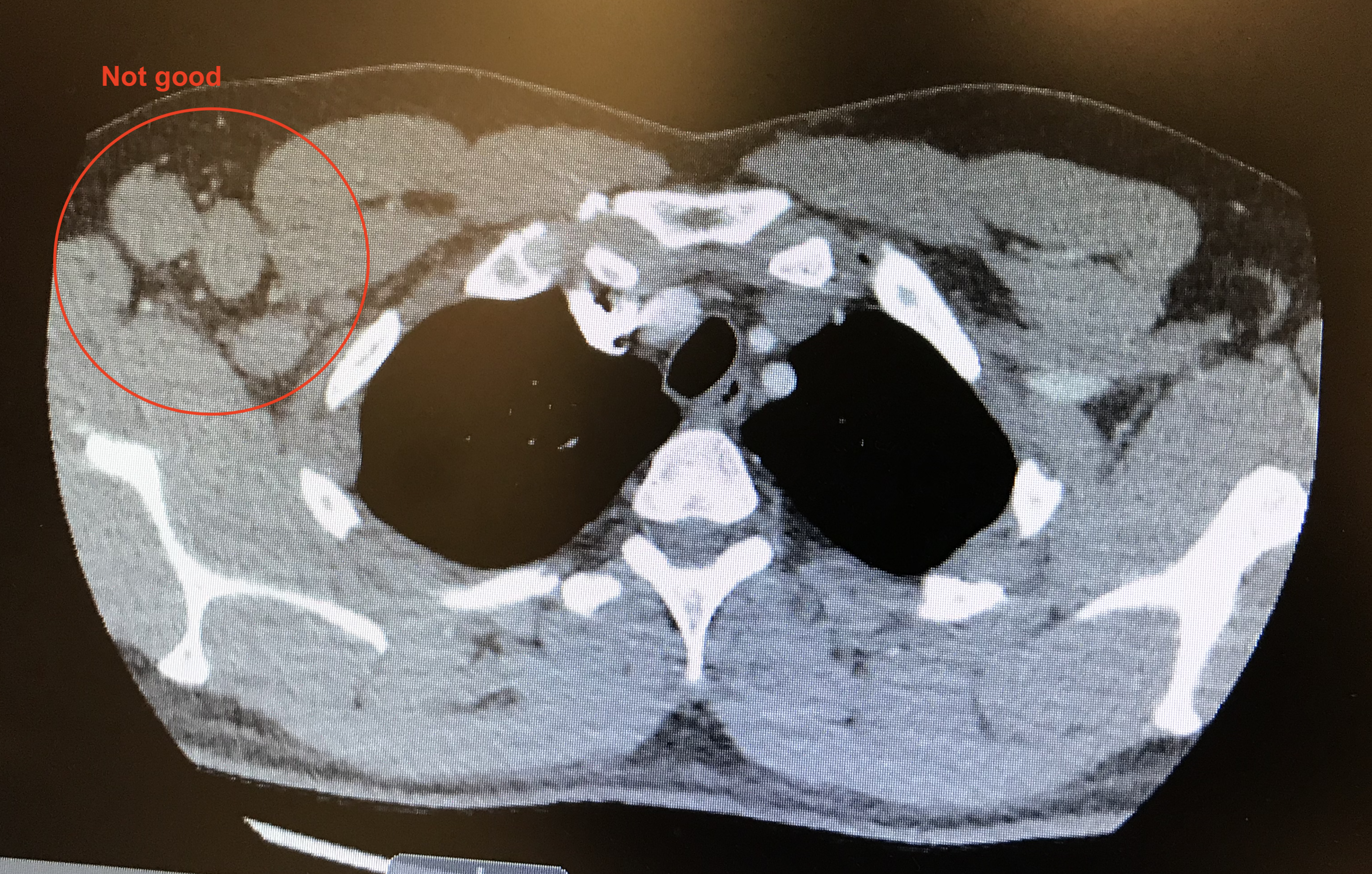

At the beginning of July, I told my lab that I had been diagnosed with nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkins lymphoma (NLPHL). In July 2018, I noticed that my right pectoral muscle wasn’t the same shape as my left. It seemed to bulge more to the side. My doctor and I didn’t think much of it. Towards the end of 2018 I noticed that the bulge in my underarm felt like a ping pong ball. Finally, I went back to the doctor for an appointment at the beginning of May and I was referred for an ultrasound. Over the next two months I had regular groping of my armpit, blood work, an ultrasound, a CT scan (see the picture above), a PET scan, a needle biopsy, and a surgical biopsy to remove an egg-sized lymph node (a few other large lymph nodes were left). On July 5th I was officially diagnosed with Stage IB NLPHL. This meant that I had a rare form of Hodgkins lymphoma that was growing slowly and was only located in my right underarm. July and August were spent planning my radiation treatments, receiving three weeks of radiation, and receiving physical therapy on my right shoulder, which had gotten torqued from the biopsy. Aside from night sweats, some hot flashes, and my shoulder, the only other symptom I noticed from this entire ordeal was fatigue caused by the radiation treatments.

Those were the symptoms I noticed. If someone asks you whether you’re experiencing extra fatigue when you’re the father of 9, a professor, and a part-time farmer, it’s kind of hard to know what to say. Tired is normal. Little did I realize, but from the beginning of May through August, I was a bundle of stress and anxiety. It built throughout the summer and with it my ability to think ground to a halt. My experience with cancer was one of contradictions. NLPHL is highly treatable and has an excellent prognosis. I am youngish (43). Up to the surgical biopsy, I was swimming 1.5 miles every morning. I knew that I would survive this. Yet the fear of leaving my wife a single mom of 9, not having enough life insurance, not having long enough paid leave, missing critical events of my family’s summer, my daughter deferring her start to college, and on and on racked me with anxiety. At the same time, I knew that I would eventually be fine. Not telling people about my health also was stressful 2. But I knew telling people would mean having to repeat my diagnosis story for each person, accepting their well-intended sympathy, receiving special treatment, and possibly being left out of events and discussions. I didn’t want to let people down, I didn’t want people to treat me differently. At the same time, I didn’t want to tell anyone.

The Monday after my treatments ended, August 19th, I noticed a weird feeling. I actually felt great. I had energy. I could think a week, month, year ahead without getting a headache. I was excited about science. I even picked a fight on Twitter! Don’t get me wrong, it will take me a bit to get back to normal, but I feel great and generally happy. All the stress and anxiety that had built up over 4 months are gone. I honestly don’t know what I did over the summer. Aside from the day of my surgical biopsy and some pre-planned “vacation”, I didn’t miss a day of work. I came in, answered emails, and… I’m not really sure what else. Yet, I know (too many) specific scientists who constantly live with this type of stress and anxiety because of life, chronic disease, and cancer. They learn to deal with it and get stuff done. From my vantage point, these people are true heroes. They are fighting their disease. I had a glimpse. A popular philosopher from when I was in grad school said, “I’m not a coward, I’ve just never been tested. I’d like to think that if I was I would pass”. Having been tested, I think I passed. Maybe not, dunno 3.

Aside from my lab, there were at most 10 people in my professional world that knew about my diagnosis. I hate sympathy, hate special attention, and certainly didn’t want anyone to treat me differently because of my lymph nodes. Evaluate me by my merits not my illness, thankyouverymuch. Every one of those people that that I told were amazing. They gave me support, checked on me, asked others to check on me, repeatedly told me to advocate for myself, and praised me even if I only got one thing done in the day. Thank you.

So why am I telling the rest of you now? I want you to know that good things happen in the world. This was a win for science. Lymphoma is scary, but thanks to modern medicine, it is treatable and many versions are considered curable. I want you to know that if something doesn’t look right or feel right that you should get it checked out. I want you to know that youngish scientists get sick. I want you to know that stress and anxiety are horrible diseases that can be more crippling than some cancers. I want you to know that every time I talked to you this summer that I left the conversation feeling guilty for not telling you. I want you to know the importance of having a strong network of friends and family that will support you and check in on you - regardless of your health status. I want you to know that you matter to me. I also feel for those that know what’s been going on but have graciously respected my privacy and don’t want them to be further burdened by me.

A few thoughts for my science friends about what I’ve taken away from this experience. First, as I look at the impact of having this brief bout of cancer on the productivity of my lab, I can see it. You probably cannot. There’s probably a lesson in that. I have a great team, amazing collaborators, and wonderful friends. Before this happened, I had gotten gotten pretty good at saying “no” to things. This helped me to learn to say “I can’t”. I simply can’t hit the fall submission deadline for that R01 I said I would submit. Second, I read one scientific paper about my disease. That paper was given to me by my doctor who knows me through work. It was a poster abstract, effectively a preprint, on treatment options that was released a few weeks earlier. We based my treatment on a preprint. Third, we don’t know what might have caused this and in many ways I don’t want to know. This particular version of Hodgkins is a fluke that tends to impact men more than women. As you can judge from my vast reading on this disease (sarcasm), I really don’t care what caused it. I feel safe saying that my microbiome had nothing to do with my cancer. Finally, I don’t really know how this event will change my specific research or professional interests. In the NCFDD bootcamps they have you outline your career as a series of chapters. Summer 2019 is certainly a chapter. I’ve been struggling to see where the plot goes from here. At the same time I have a deep affection for the patients, therapists, nurses, and doctors that I interacted with throughout the ordeal. As one reads my life story, these health care providers may appear to be minor characters, but they have changed my life and will not be forgotten.

There are many more little stories that I could tell you about what I’ve learned and about my personal journey with cancer. Most of these are very personal and I haven’t really had the ability to process them myself. My biggest source of stress was the impact that me being sick would have on my family. I am eternally grateful that of all the ways this could have impacted my family, they have all been positive. I didn’t miss a thing that we had planned on doing - 4H, taking my daughters to a ram sale in Ohio, hosting family from out of town, and driving my eldest to start college. My kids chipped in when I couldn’t use my arm or was too tired to be of any use. It seems that even at home I learned to say, “I can’t”. At the end of it all, my family joined me at my final radiation treatment to ring a bell signaling the end. I could not have gone through this without them. More than anything this experience has emphasized for me that my job is a job that affords me great benefits, wonderful quality of life, access to great colleagues who are also amazing clinicians, and excellent professional opportunities. But in the end, it’s a job. My family, friends, and experiences are irreplaceable.

~~~~~

-

If you’re going to read this or talk to me about it, there is going to be a rule. Do not tell me that you’re sorry. Don’t be sorry. It wasn’t your fault. Anyway, it’s over. Having people tell me they’re sorry only makes me feel depressed. Don’t tell me you’re sorry. Don’t. If you need to say something, tell me I passed. ↩

-

First, I am sorry that I didn’t tell you, but don’t feel bad that you feel left out. This is harsh, but it wasn’t about you. Me deciding to tell you or not was about me. I needed to have some control. All the while, I was very much not in control. I was hanging on. I was doing what I could. ↩

-

At least at UM, when you lay on the bed during radiation they offered to create a Spotify playlist. Throughout this ordeal, The Impression that I Get, became my personal theme song because of these lines. So I asked the radiation therapists to make a Mighty Mighty Bosstones playlist. I didn’t realize that this would show my age to the therapists who had never heard of the band! ↩